Quinn River Cutthroat

Oncorhynchus henshawi ssp.

A stream resident Quinn River Cutthroat from a Nevada stream.

Introduction

The Quinn River Cutthroat are a subspecies of Lahontan Cutthroat native to the Quinn River drainage of northern Nevada and southeastern Oregon. At times the Quinn River Cutthroat have been lumped with both the Lahontan Cutthroat and Humboldt Cutthroat subspecies, as they have intermediate traits between the two (Behnke 1992, Behnke 2002, Trotter and Behnke 2008). However, recent genetic evidence suggests that they are distinct enough to warrant being considered their own subspecies (Peacock et al. 2018, Trotter et al. 2018). While the Quinn River Cutthroat warrants subspecies status, fisheries manageners often simply consider it as Lahontan Cutthroat, likely due to it not being separated from Lahontan Cutthroat in its Endangered Species Act listing and the only recent genetic understand of its distinctiveness.

Life History Information

Historically, the Quinn River Cutthroat likely exhibited both stream resident and fluvial life histories, however all but a few isolated populations of Quinn River Cutthroat Trout have been lost and now only pure stream resident populations remain. Although there may be some limited expression of the fluvial life history in the hybrid populations in the McDermitt Creek watershed. The Quinn River Cutthroat are thought to have a similar life history to that of the Humboldt Cutthroat and are opportunistic feeders, primarily preying on aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates. Like Humboldt Cutthroat, stream resident Quinn River Cutthroat have been observed in streams with daily temperatures up to 83.3° F (28.5° C) (Dunham et al. 2003) and are able to survive daily fluctuations in water temperature of over 40° F (22° C) (Sevon et al. 1999). Quinn River Cutthroat appear to favor habitat in areas where streams transition from canyons to more open valley floors (Boxall et al. 2008). These areas tend to have increased number of pools as well as ground water inputs providing trout with refuge habitat from high summer temperatures and ice in the winter. It is thought that stream resident Quinn River Cutthroat have a maximum size of around 8” to 9” (20 cm to 23 cm) and spawn for the first time at age-2 to age-3 (Behnke 2002, Trotter 2008). Spawning typically ocurrs when water temperatues exceed 45° F (7.2° C) in late-May to early June, with females depositing around 200 eggs (Sevon et al. 1999). Fry typically emerge within 8 to 10 weeks of spawning and utilize riffles, glides, small pools or off channel habitat as nursey areas. While Quinn River Cutthroat are iteroparous, few typically survive spawning, and it is thought that most fish only live to be three or four years old (Sevon et al. 1999).

Status

As with other subspecies of Lahontan Cutthroat Trout, the Quinn River Cutthroat have suffered significant declines and were limited to just a handful of small native populations remaining prior to conservation efforts beginning. As a result of their decline, the Quinn River Cutthroat were listed along with the other Lahontan Cutthroat subspecies as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act in 1970, although they were down listed to threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1975 to increase the feasibility of restoration efforts (USFWS 1970, USFWS 1975). When the Nevada Department of Wildlife surveyed the Quinn River basin between 1935 and 1960, they found Cutthroat in approximately 398 miles (640 km) of habitat spread across 20 streams (Trotter 2008). It is likely that the Quinn River Cutthroat was historically native to significantly more habitat as poor land use practices and excessive water withdrawls had already severely degraded much of the potential habitat in the basin by this point. By the late-1980’s pure populations of Quinn River Cutthroat were thought to inhabit less than 2% of their historic habitat at less than 16 miles (26 km) of occupied streams (Sevon et al. 1999). By 1995, Quinn River Cutthroat were known to be found in just 14 streams, with some of these populations being composed of hybrids. However, as of the 2009 status review it appears as through no significant progress has been made in recoverying these fish as five of these 14 populations had been lost, while at the same time reintroduction efforts had established populations in five other streams across the basin (USFWS 2009). Given how few populations remain and the isolated nature of most the populations, the loss of any original native populations is particularly determental as it often results in the loss of unique phenotypes and genetic characteristics. As such, Peacock and Kirchoff (2004) expressed the importance of preserving every remaining population of Quinn River Cutthroat, even those that have a limited amount of introgression with hatchery Rainbow Trout. Based on recent surveys, it is thought that Quinn River Cutthroat are currently found in about 15% of their historical habitat (NDOW 2012).

The primary factors leading to the decline of the Quinn River Cutthroat have been the introduction of non-native salmonids, waterwithdrawls and poor land use practices, especially from freerange grazing. Non-native salmonids were stock indiscriminately throughout the Quinn River basin with the first documented stocking of hatchery Rainbow Trout occurring in 1896 (Sevon et al. 1999). Non-native trout present risks to Quinn River Cutthroat via competition, predation, and hybridization. Brook Trout and Brown Trout have been stocked in many of the streams and as they spawn in the fall, juveniles of these two species get a competitive advantage over the spring spawning Quinn River Cutthroat. The introduction of hatchery Rainbow Trout has been one of the most significant threats as they readily hybridize with Quinn River Cutthroat and have been stocked throughout much of their native range (USFWS 2009). The combination of excessive waterwithdrawls and poor grazing practices has resulted in many streams being dewatered and reaching temperatures that are inhospitable to trout. These effects have resulted in isolated populations that would have formerly be connected, as well making populations more susceptible to being lost during drought years.

The most ambitious restoration project for Quinn River Cutthroat is in the McDermitt Creek, where the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) as well as the Nevada Department of Wildlife (NDOW) are attempting to restore Quinn River Cutthroat to the entire 50 miles (80 km) of habitat in the drainage. Genetics sampling paired with a population survey in the late 1990’s indicated that the McDermitt Drainage was dominated by Rainbow Trout-Cutthroat hybrids, with 4,135 hybrids and 1,791 pure Cutthroat in the basin (Peacock and Kirchoff 2004). As the watershed represents the best interconnected drainage in the Quinn River basin to reestablish a fluvial population, between 2006 and 2009 fisheries managers treated the watershed to remove all non-native salmonids. ODFW planned to release pure Quinn River Cutthroat back into the treated reaches in 2013, but unfortunately someone else beat them to it and illegally reintroduced Rainbow Trout and Brook Trout back into the watershed. Since that point, the restoration Lahontan Cutthroat population has stalled out an its future is uncertain. However, in 2020 the Western Rivers Conservancy purchased the 3,345 acre Disaster Peak Ranch in the upper McDermitt watershed, which will hopefully make the restoration of Quinn River Cutthroat in McDermitt Creek feasible in the near future.

Description

Among the Lahontan Cutthroat subspecies, Quinn River Cutthroat Trout are likely most similar in appearance to the Alvord Cutthroat Trout, although the appearance can be quite variable. The coloration of these fish is often olive-bronze to copper color on the back which transitions to a yellow color often with an intense red or pink on the side and gill plate and a pale yellow or white color on the belly. The lower fins range from brown to purple in color and the caudal, dorsal, adipose and anal fins all may be spotted. These Cutthroat typically have relatively large round spots, that are most concentrated towards the tail, and predominately above the lateral line, although some fish may have spots below the lateral line as well. There are usually some spots on the head as well and parr marks are often retained into maturity. As with other Cutthroat Trout, a red to to orange slash is found below the jaw.

Stream Resident Form

Click on images to view a larger picture

Native Range

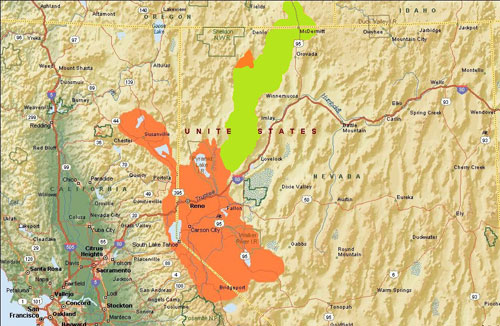

A map of the native range of the Lahontan Cutthroat Trout (orange) and the Quinn River Cutthroat formley included with the Lahontan Cutthroat (green). Data Source: Behnke (2002) and Trotter (2008).

References

Behnke, R. J. 1992. Native trout of western North America. American Fisheries Society Monograph 6. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Behnke, R. 2002. Trout and Salmon of North America. Chanticleer Press, New York.

Boxall, G.D., G.R. Giannico and H.W. Li. 2008. Landscape topography and the distribution of Lahontan cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi) in a high desert stream. Environmental Biology of Fish 82:71–84.

Dunham, J., R. Schroeter and B. Rieman. 2003. Influence of maximum water temperature on occurrence of Lahontan cutthroat trout within streams. North American Journal of Fisheries Management 23: 1042–1049.

Peacock, M.M. and V. Kirchoff. 2004. Assessing the conservation value of hybridized cutthroat trout populations in the Quinn River drainage, Nevada. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 133:309–325.

Peacock, M.M., H.M. Neville and A.J. Finger. 2018. The Lahontan basin evolutionary lineage of cutthroat trout. Pages 231–259 in P. Trotter, P. Bisson, L. Schultz and B. Roper editors. Cutthroat trout: evolutionary biology and taxonomy. American Fisheries Society Special Publication 36. American Fisheries Society. Bethesda, Maryland.

Sevon, M., J. French, J. Curran and R. Phenix. 1999. Lahontan cutthroat trout species management plan for the Quinn River/ Black Rock basins and North Fork Little Humboldt River sub-basin. Nevada Department of Wildlife, Carson City, NV.

Trotter, P. 2008. Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West. Second Edition. University of California Press, Berkley, CA.

Trotter, P.C. and R.J. Behnke. 2008. The case for humboldtensis: a subspecies name for the indigenous cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii) of the Humboldt River, upper Quinn River, and Coyote Basin drainages, Nevada and Oregon. Western North American Naturalist, 68(1): 58-65.

Trotter, P., P. Bisson, B. Roper, L. Schultz, C. Ferraris, G.R. Smith and R.F. Stearley. 2018. A special workshop on the taxonomy and evolutionary biology of cutthroat trout. Pages 1-31 in Trotter P, Bisson P, Schultz L, Roper B (editors). Cutthroat Trout: Evolutionary Biology and Taxonomy. Special Publication 36, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

USFWS. 1970. United States List of Endangered Native Fish and Wildlife. Federal Register 35:16047-16048.

USFWS. 1975. Threatened Status for Three Species of Trout (Lahontan cutthroat, Salmo clarki henshawi; Paiute cutthroat, Salmo clarki seleniris; Arizona trout, Salmo apache). FR 40:29863-29864.

USFWS. 2009. Lahontan cutthroat trout, Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi, 5-year review: summary and evaluation. United States Fish and Wildlife Service. Reno, Nevada. 198 pp.

Contact

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or comments

Quinn River Cutthroat Trout Links

Nevada Department of Wildlife - Lahontan Cutthroat

Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest

Bureau of Land Management - Black Rock Desert Wilderness Area

Western Rivers Conservancy - McDermitt Creek

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service - Lahontan Cutthroat

Western Native Trout Initiative - Lahontan Cutthroat Trout

Native Trout Links

Truchas Mexicanas' - Native Trout of Mexico

Balkan Trout Restoration Group

Trout and Seasons of the Mountain Village - About Japanese Trout

Western Native Trout Challenge

California Heritage Trout Challenge

Fly Fishing Blogs

Dave B's Blog: Fly Fishing for Native Trout

The Search for Native Salmonids

Conservation Links

Western Native Trout Initiative

Fly Fishing Links

Fishing Art Links

Americanfishes.com - Joseph R. Tomelleri