St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat

Oncorhynchus lewisi ssp.

A fluvial St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat from an Idaho stream.

Introduction

The St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat Trout are native the St. Joe watershed in the Panhandle region of northern of Idaho. Based on genetics, Westslope Cutthroat from the Neoboreal subspecies are found in the lower reaches of the Coeur d’Alene and St. Joe watersheds and it is unclear what mechanisms separate them from the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat or if these Neoboreal fish are native to the watersheds (Young et al. 2018). Morphologically, the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat are very similar to other Westslope Cutthroat and as such were lumped the rest of the Westslope Cutthroat as a single subspecies Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi (Behnke 1992, Behnke 2002). However, recent evidence indicates that St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat are genetically distinct enough warrant subspecies status (Trotter et al. 2018, Young et al. 2018).

Life History Information

The St. Joe River Westslope Cutthroat exhibit stream resident, fluvial (river migrant) and possibly adfluvial (river to lake migrant) life histories, although it is unclear whether adfluvial fish represent the St. Joe or Neoboreal subspecies. Stream resident Cutthroat are typically found in tributaries to the St. Joe River, often 2 to 3 miles (3 to 5 km) upstream of the confluence with the mainstem, while fluvial fish utilize the lower reaches. Stream resident fish are opportunistic drift feeders preying aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates, typically reaching a maximum size of 12” (30 cm). In contrast, fluvial fish are known to reach sizes of up to 20” (50 cm) preying on aquatic and terrestrial invertebrates as well as fish. These fluvial fish typically have a maximum life span of six years and spend their first two to three years in tributaries prior to migrating downstream to the mainstem St. Joe River during the summer (peak of migration in July) at a size of 5” to 5.5” (13 to 14 cm) (Rankel 1971). Throughout the summer months these Cutthroat move little, holding in runs, riffles, or pocket water areas. However, during September to October, fluvial fish migrate downstream up to 60 miles (96.5 km) into deep pools that serve as overwintering habitat (Rankel 1971). Spawning takes place between late-April and mid-May when males reach age-2 to age-3 and females are age-3 to age-4.

Within the St. Joe watershed approximately 5% of the Cutthroat exhibit an adfluvial life history (Heckel et al. 2020). Adfluvial juveniles typically emerge around two months after being spawned and spend 1 to 4 years in tributaries before migrating to the lake at a size of 7” to 9” (18 cm to 23 cm) (Trotter 2008). Adfluvial Cutthroat migrate downstream into Lake Coeur d’Alene in June, where they spend 2 to 3 years foraging prior to migrating upstream to spawn at age-5 to age-6, although age-3 spawners have been observed as well (Trotter 2008). Upstream migrations into the river observed between December and April and the spawn timing and size at maturity are thought to be similar to that of fluvial fish (Behnke 2002, Dupont et al. 2008).

Status

Historically the abundance of the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat was greatly reduced, primarily due to overfishing and habitat impacts, and the recovery of these Cutthroat represents one of the great native trout conservation success stories. Today, the St. Joe River represents one of the major strongholds of Westslope Cutthroat, and the St. Joe subspecies are abundant and relatively stable in the watershed. While the St. Joe River population is thriving, the St. Maries population has lagged behind as, habitat impacts continue to limit the abundance of Cutthroat Trout in the watershed.

The primary limiting factor for Cutthroat in the St. Joe River was overfishing. Due to the low productivity of the watersheds that Westslope Cutthroat are found, these trout are extremely opportunistic feeders and are known for being far more susceptible to angling than other species of trout (Behnke 1979, Paul et al. 2003). This angling susceptibility coupled with the slow maturation also makes their populations particularly prone to declines due to overharvest. Early anglers on the St. Joe River viewed the populations as being inexhaustible and as such overharvest was inevitable. Turn of the century reports from the St. Joe River document anglers harvesting up to 35 lbs. (15.9 kg) of Westslope Cutthroat in just one hour of angling (Mallet and Thurow 2021). Many of the harvested Cutthroat were destined for commercial markets in Spokane and other nearby cities, a practice that clearly not sustainable. To help stem this uncontrolled harvest, one of the first actions taken by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game (IDFG) in 1899 when it was formed was to ban the commercial sale of trout and other game fish (Mallet and Thurow 2021). Despite an early recognition of the unsustainable nature of runaway harvest on Westslope Cutthroat, liberal bag limits continued for years until anglers began to voice dissatisfaction with the deteriorating fisheries.

In response to the deterioration of the fishery, IDFG began to study Cutthroat in the St. Joe River to inform management and also began to stock nonnative Rainbow Trout, Brook Trout and Yellowstone Cutthroat to supplement harvest (Mallet and Thurow 2021). Despite the promise of “improved” fishing from stocking, anglers expressed a preference for native Cutthroat (Rankel 1971), which likely influenced lower stocking levels than seen in other states. However, stocking of hatchery Rainbow Trout still occurred throughout the native range of the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat Trout for many years, with the last releases being in the St. Maries River in 2002 (IDFG 2013). Fortunately, the impacts for these introductions appear to have been minimal and Rainbow Trout and Cutthroat x Rainbow Trout hybrids are only occasionally encountered in the St. Joe and St. Maries drainages. The other major non-native salmonid introduced to the St. Joe and St. Maries drainages were Brook Trout and these introductions were much more successful at establishing self-sustaining populations, especially in the North Fork St. Joe River, lower St. Joe tributaries and the St. Maries watershed (IDFG 2013). Brook Trout, which are fall spawners are problematic primarily due to competition with Westslope Cutthroat particularly early in their life cycle. Work on other Westslope Cutthroat subspecies has shown that age-0 Brook Trout, which emerge during early summer are larger and maintain a competitive advantage of Westslope Cutthroat which emerge in late summer (Shepard et al. 2002). This has resulted in a complete or near complete replacement of Westslope Cutthroat by Brook Trout in many watersheds, especially small tributary streams. In th St. Joe drainage, Brook Trout have typically been observed outnumbering Cutthroat in meadow reaches and the lower reaches of tributary streams (Thurow and Bjornn 1978). There is still room for improvement with the impacts of nonnative salmonids, especially Brook Trout in the St. Joe and St. Maries watersheds, but fortunately the persistence of the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat has not been compromised by these introduced fish. To encourage suppressing the populations of these nonnative trout, IDFG has promoted liberal harvest limits of Brook and Rainbow Trout.

Instead of putting the primary focus of improving fisheries in the St. Joe River on hatchery stocking, IDFG began assessing Cutthroat densities and evaluating the response of Cutthroat to changes in fishing regulations. In the late-1960’s when IDFG began studying the Cutthroat population in the St. Joe watershed, they noted that the abundance, size, survival rate and proportion of mature females had declined in the watershed indicating that the population was overexploited and at risk of extinction (Rankel 1971). In response, IDFG reduced the limit on Westslope Cutthroat in the upper watershed to 3 fish > 12” (30 cm) per day. This reduced harvest resulted in a 3-5-fold increase in Cutthroat abundance and a 12-fold increase in catch rates from the late-1960’s to 1975 (Johnson and Bjornn 1978). Another of the early regulatory actions was to close several tributaries to the St. Joe River to angling. The tributary closure proved to be particularly effective and resulted increased numbers of fry as well as more and larger adult Cutthroat utilizing the streams (Thurow and Bjornn 1978). Based on the success of these early efforts, catch and release regulations were adopted for Cutthroat in 1988 in the upper watershed and expanded to the entire watershed in 2008. The result of these shifts to more conservation minded management has been an increase of Cutthroat densities of less than 0.50 fish/ 100 m2 over 12” (30 cm) in the late-1960’s to ~ 2.0 fish/ 100m2 over 12” (30 cm) by 2012 (IDFG 2013).

While over-fishing was the primary driver in the decline of Cutthroat in the St. Joe River, habitat impacts also played a role and continue to impact these Cutthroat across much of their native range. Early habitat impacts came from a variety of sources, including logging and splash dams, mining and railroad and road building activities. Historical records note that during the construction of the railroad in the St. Joe watershed the St. Joe River ran muddy throughout the period of the project, with the plume extending well into Lake Coeur d’Alene (IDFG 2013). The construction of the railroads and later the highways in both the St. Joe and St. Maries Rivers resulted numerous migratory barriers and stream armoring impeding habitat complexity. Logging represented another significant habitat impact and effects were particularly pronounced in the riparian corridor, where vegetation loss resulted in increased water temperatures and sedimentation. Historically, splash dams were employed on a number of tributaries. These dams were used as a strategy to transport logs downstream to Lake Coeur d’Alene and resulted in barriers to fish passage and a significant amount of scour and sedimentation. Marble Creek in particular was impacted heavily by splash dams and the legacy impacts are still readily apparent (IDFG 2013). Today many sections of the St. Maries River are still actively mined, resulting in the clearing of the floodplain as well as relocation of stream channels (IDFG 2013). Fortunately, land practices have improved over the years and the upper reaches of the St. Joe watershed and parts of the St. Maries watershed are on Forest Service land where management is more focused on maintaining a healthy ecosystem. Thanks to the lessons learned from past mistakes and the conservation minded approach to fisheries and improving land management practices, today the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat have a bright future.

Description

The St. Joe River Westslope Cutthroat Trout are similar in appearance to other Westslope Cutthroat. The coloration on the backs and sides of these fish is typically an olive, bronze or even grayish color. The side of these fish range from a grayish color to tan or bronze and the bellies and gill plates typically show a peach to bright orange or even red color. This same red color may be found along the lateral line, often between the parr marks on immature individuals. Spots are typically irregularly shaped, small to medium sized and concentrated towards the posterior region of the body and along the back with relatively few spots found below the lateral line in the middle of the body. Their fins typically are a yellow to orange or peachy color and spots are typically found on the dorsal, adipose and caudal fins.

Fluvial Form

Click on images to view a larger picture

Native Range

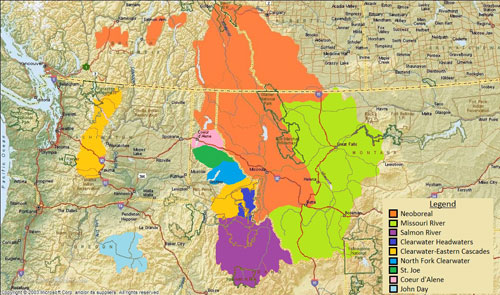

Above: A map of the native range of the Westslope Cutthroat trout. Data Sources: Behnke (2002), Trotter (2008) and Young et al. (2018). Below: A map of the native range of the St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat Trout.

References

Behnke, R.J. 1979. Monograph of the native trouts of the genus Salmo of western North America. U.S.D.A. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Lakewood, Colorado.

Behnke, R. J. 1992. Native trout of western North America. American Fisheries Society Monograph 6. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Behnke, R. 2002. Trout and Salmon of North America. Chanticleer Press, New York.

Heckel, J.W., M.C. Quist, C.J. Watkins and A.M. Dux. 2020. Life history structure of westslope cutthroat trout: inferences from otolith microchemistry. Fisheries Research 222: 105416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2019.105416

IDFG. 2013. Management plan for the conservation of Westslope Cutthroat Trout in Idaho. Idaho Department of Fish and Game. Fisheries Bureau, Boise, Idaho.

Johnson, T.H. and T.C. Bjornn. 1978. Evaluation of angling regulations in management of cutthroat trout. Project F-59-R-7. Idaho Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit. University of Idaho, Moscow, Idaho.

Mallet, J. and R.F. Thurow. 2021. Resurrecting an Idaho icon: how research and management reversed declines of native Westslope Cutthroat Trout. Fisheries DOI: 10.1002/fsh.10697

Paul, A.J., J.R. Post and J.D. Stelfox. 2003. Can anglers influence the abundance of native and nonnative salmonids in a stream from the Canadian Rocky Mountains? Journal of North American Fisheries Management 23:109–119. https://doi.org/10.1577/1548-8675

Rankel, G. 1971. Life history of St. Joe River Cutthroat Trout. Idaho Department of Fish and Game, Federal Aid in Fish Restoration, Project F-60-R-2, Annual Completion Report, Boise.

Shepard, B.B., R. Spoon and L. Nelson. 2002. A native westslope cutthroat population responds positively after brook trout removal and habitat restoration. Intermountain Journal of Sciences 8(3) 193-214.

Thurow, R.F. and T.C. Bjornn. 1978. Response of Cutthroat Trout populations to the cessation of fishing in St. Joe River tributaries. Idaho Fish and Game, Boise, ID.

Trotter, P. 2008. Cutthroat: Native Trout of the West. Second Edition. University of California Press, Berkley, CA.

Trotter, P., P. Bisson, B. Roper, L. Schultz, C. Ferraris, G.R. Smith and R.F. Stearley. 2018. A special workshop on the taxonomy and evolutionary biology of cutthroat trout. Pages 1-31 in Trotter P, Bisson P, Schultz L, Roper B (editors). Cutthroat Trout: Evolutionary Biology and Taxonomy. Special Publication 36, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Young, M.K., K.S. McKelvey, T. Jennings, K. Carter, R. Cronn, E.R. Keeley, J.L. Loxterman, K.L. Pilgrim and M.K. Schwartz. 2018. The phylogeography of westslope cutthroat trout. Pages 261-301 in Trotter P, Bisson P, Schultz L, Roper B (editors). Cutthroat Trout: Evolutionary Biology and Taxonomy. Special Publication 36, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Contact

Feel free to contact me if you have any questions or comments

St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat Trout Links

My St. Joe Westslope Cutthroat Trips

Idaho Department Fish and Game - Westslope Cutthroat Trout

Western Native Trout Initiative - Westslope Cutthroat Trout

Native Trout Links

Truchas Mexicanas' - Native Trout of Mexico

Balkan Trout Restoration Group

Trout and Seasons of the Mountain Village - About Japanese Trout

Western Native Trout Challenge

California Heritage Trout Challenge

Fly Fishing Blogs

Dave B's Blog: Fly Fishing for Native Trout

The Search for Native Salmonids

Conservation Links

Western Native Trout Initiative

Fly Fishing Links

Fishing Art Links

Americanfishes.com - Joseph R. Tomelleri